The Theo Bikel Yiddish-Into-English International Poetry Translation Contest

דער 2017 אינטערנאַציאָנאַלער ייִדיש־צו־ענגליש איבערזעצונגס קאָנקורס

Call for entries:

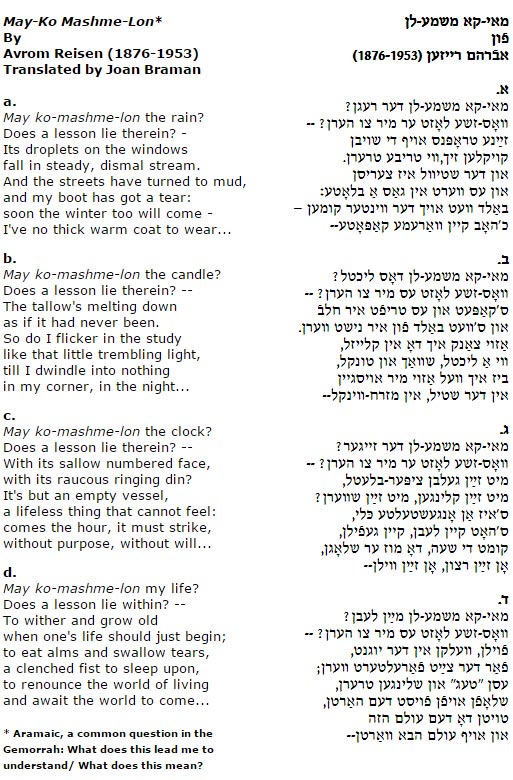

Calling all poetry mavens! Do you have a favorite Yiddish poet or a poem that has yet to reach the English-speaking masses? Or have you come across a published translation of a wonderful Yiddish poem that perhaps mangles the poetic intentions of its creator? This is your chance for redemption. Find that special poem that you would like shared with a wider audience and make it come alive. Just as the Golem rose to life by the sacred words of its creator, breathe new life into your Yiddish poem of choice. Dazzle us with your cross-cultural understanding of the Yiddish and English languages. Impress us with your knowledge of the delicate intricacies and nuances of the mameloshn.

Calling all poetry mavens! Do you have a favorite Yiddish poet or a poem that has yet to reach the English-speaking masses? Or have you come across a published translation of a wonderful Yiddish poem that perhaps mangles the poetic intentions of its creator? This is your chance for redemption. Find that special poem that you would like shared with a wider audience and make it come alive. Just as the Golem rose to life by the sacred words of its creator, breathe new life into your Yiddish poem of choice. Dazzle us with your cross-cultural understanding of the Yiddish and English languages. Impress us with your knowledge of the delicate intricacies and nuances of the mameloshn.

First place winners will be announced in April. The first place winner will receive $100, plus publication on the CIYCL website and newsletter. Second place winners will receive $50 plus publication on our website. This contest is sponsored by Lee Chesnin, and CIYCL Board Member Stephen O. Lesser.

Contest Rules: Your single entry of up to two pages must include a copy of the original Yiddish poem (in Yiddish characters) and your own, never before published English translation. Entries over the required length will be disqualified.

Submissions must be received by March 20, 2017.

For submissions by mail:

CIYCL, 333 Washington Blvd., #118,

Marina del Rey, CA 90292

For submissions by e-mail: [email protected]

Past Winners

|

THE BALLAD OF MY LULLABY Once on a wintry evening, when the lamp was not yet |

(1924) פֿון משה-לײב האַלפּערן, 1886-1932 אײנמאָל אין אַ װינטערדיקן פֿאַרנאַכט, דער לאָמפּ איז נאָך נישט געװען אָנגעצונדן, האָב איך געװײנט װי אַלע קלײנע ייִנגעלעך פֿאַרן שלאָפֿנגײן, האָט מיך די באָבע גענומען אױפֿן שױס, און אָט װאָס זי האָט מיר דערצײלט׃ — אַמאָל איז געװען אַ מלך װאָס האָט ליב געהאַט יונגע ציבענקלעך. נאָר אַזױ װי ער איז געװען אַ גרױסער עקשן, אַ גרױסער עקשן, האָט ער זיך אײַנגעשפּאַרט אַז ער װיל ציבענקלעך מיט רױטע בערשטעלעך. — װאָס-זשע האָט מען געטאָן? — האָט מען צעשיקט שלוחים איבער דער װעלט, שלוחים איבער דער װעלט. האָבן אָבער די שלוחים געבלאָנדזשעט אַזױ לאַנג ביז זײ זײַנען אָנגעקומען קײן פּראָמישלאַן צום פֿעטער רב לײבישל. איז דאָך דער פֿעטער רב לײבישל געװען אַ בערשטלמאַכער אַ בערשטלמאַכער האָט ער אַרױסגענומען פֿון זיבן בינטלעך ציבענקלעך די װײַסע בערשטעלעך און אַרײַנגעפֿלאָכטן אַהין די פֿרענזלעך פֿון זײַן שאַליקל פֿון זײַן רױטן שאַליקל װאָס ער איז געגאַנגען אַרום האַלדז װינטער און זומער און אַלע זײַנע יאָרן. און אַזױ איז געשען, אַז װי נאָר ער האָט זיך געזענגט מיט װײַב און קינד, איז ער אַװעק מיט די שלוחים צו דער שטאָט, צו דער װײַטער און שײנער, און גאָלדענער שטאָט װוּ דער מלך האָט געװױנט, מלך האָט געװױנט. אָבער זינט דעמאָלט טאַקע האָט מען מער נישט געהערט פֿון אים, מער נישט געהערט פֿון אים. אַזױ װי אין װאַסער אַרײַן איז ער — — — אַזױ װי אין װאַסעראַרײַן — — — נאָר אַז איך, װאָס בין נאָך דעמאָלט געװען אַ קלײן ייִנגעלע, האָב נאָך אַלץ געװײנט. האָט די באָבע פֿאַרענדיקט אַז דער פֿעטער רב לײבישל איז געװאָרן באַם מלך, אַ גרױסער חשובֿ, גרױסער חשובֿ. און זי האָט אױסגעלאָזט מיט דעם אַז דער מלך האָט געהאַט אַ טעכטערל זײער אַ שײן טעכטערל, האָט אָבער אײנמאָל די ניאַנקע זיך פֿאַרקוקט אױף אַן עלטסטן מיט אַ געלן שפּענצער, איז דאָס טעכטערל אַראָפּגעפֿאַלן פֿונ׳ם בױדעם, און פֿון דעמאָלט אָן טאַקע, װען עס קומט דער ליבער פּורים דער ליבער פּורים, און זי װיל זאָגן גיב מיר אַ שטיקעלע פּורימ-קױלעטש, שטרעקט זי אױס דאָס העלדזעלע און זי זאָגט׃ גיב מיר אַ שטיקעלע פּו. גיב מיר אַ שטיקעלע פּו-פּו. גיב מיר אַ שטיקעלע פּו-פּו-פּו. און װײַטער קען זי נישט — — — און װײַטער קען זי נישט — — — די באַלאַדע פֿון מײַן װיגליד, |

[1]The poet Moyshe-Leyb Halpern (1886-1932) came to New York from Poland in 1908. Originally associated with the literary group Di Yunge, he also contributed to satirical magazines, where he cultivated the role of rebel and social critic. His internal struggle between tender concern and disgust for the human condition expressed itself in increasingly complex imagery. He is often considered the most original and distinctive voice in Yiddish poetry.

|

When The Surgery Is Over The scalpel knows |

נאָכן כירורגישן טיש [1] דאָס מעסערל װײס [1] ”הייַנט”, נ. 203 , פֿון 1טן סעפּטעמבער 1939 |

[1]The poem is remarkable for expressing accurately and sensitively the foreboding and trappedness felt by people at the time, as well as the desperate wish for a heaven-sent explanation and solution. The central trope is a comparison of Polish Jewry’s situation after 1938 to an isolated, helpless anaesthetized body waiting to be cut up. Will it be put together again, he asks? We have chosen the “sleeping potion” rather than face the truth. Stern puts forward two readings of this state of affairs. In the first, we are material creatures only and will be dealt with like stupid plant matter. The other alternative is that we are our Father’s children andHe is testing us. We can still repent in time, though on the verge of death – and will experience a new beginning.

|

Efraim Goldbrukh (Ostrolenka) I “If you see your light lie buried Who knows, then, what his sadness means? Just as one who lies at the feet II A fine, upstanding Jew — they said, Roofs kiss each other tenderly and scarcely move. The night bathes itself with wind, “Even with a wife, a bed, and a big house, III You sleep somewhere like a beggar on a sack, yourself a sack. stands tall, all alone, awaiting no owner It’s dangerous for someone who doesn’t know And your kapote, Mr. Goldbrukh, is really no river, Is that normal? Leave such things in a drawer. IV So, alright, now it’s Friday, everyone knows: And at Yosel the cobbler’s they’re dying for lack of food. And when evening adds tongues of flame And Widow Leahke has to sit in darkness? So, anyway, it’s Friday, and you understand V The clouds mingle and riffle by without a sound. Obediently, the streets become more pure. The town has shaken sleep from its eyes And what does Efraim Goldbrukh do? Noontime lies across the world, burning with anger and ashamed; Goods go to market, the sun goes through the sky, And what does Efraim Goldbrukh do? Yet the day has ended even more beautifully than it began. enclosing a king’s domain… and bent in pious contemplation And Khatzkel Kupfermintz doesn’t understand what suddenly is with him. And what does Efraim Goldbrukh do? VI Reb Efraim! Reb Efraim! People look the world in the mouth, If on the other side a tooth falls out, One weighs a heart out slowly on the scale, VII And Efraim Goldbrukh answers: |

אפּֿרים גאָָלדברוך (אָסטראָלענקע) דד//’ראטא פּונקט װי אײנער, װאָס ליגט צופֿוסנס זײַן קאָפּ מיט טונקל, װי באַנדאַזשן, מיט לאַנגע מעסערס, װי לאַנגע יאָר, מיט ליכט אַראָפּ אױף טראָטואַרן, ליגן אַלע זײַנע יאָרן און ער אַנטלױפֿט (װי דער הימל זײַן גאַנץ פֿאַרמעגן איז פֿאַרברענט, איז אױכעט פֿאַלש און רײַבט זיך אָפּ…) בײַ דער לױה פֿון איר קינד, און בײַ יעדן טריט רױמט דער װינט אַז װעסט זען דײַן ליכט באַגראָבן, און דײַנע איבעריקע קינדער און ער אַנטלױפֿט און טוקט זיך אונטער אפֿשר האָט ער שװערע זינד, טובלענדיק זיך און געלײַטערט, — װײַל װי לאַנג ס׳װאָל איז נישט געשױרן, און אױב ער האָט שױן אַלץ פֿאַרלױרן, װער װײס דען, װאָס זײַן טרױער מײנט? בײַ פֿאַרשטױסן פֿרעמדן פּלײן, האַלט ער אין פֿינצטערניש פֿאַרװיקלט האָט די װעלט אים, און ער װײנט. מיט אַ לאַמטערן אין דער האַנט. און אַנטלױפֿן אין די זײַטן, װילן אַ רעטער דאָ געפֿינען צום עלנדטרױעריקן, װאָס ליגט, פּונקט װי אײנער, װאָס ליגט צופֿוסנס זײַן קאָפּ מיט טונקל, װי באַנדאַזשן, װײסן נישט דערפֿון און ריכטן אַזױ קומט איר צו מיר, געזיכטער מיט אַראָפּגעלאָזטע קעפּ, נאָר פֿון אײַך אַלע איז געװאָרן II װי מ׳זאָגט האַלב-חודש׃ ס׳אַר אַ שײנע נאַכט! און האָסט קײן הײם נישט געהאַט. דער הימל צאַפּלט זיך װי אַ בלאָער עוף. עס שטײט שױן איצט דיִ שטאָט ביזן האַלדז אין שלאָף. און שפּיגלט זיך אין שטילע גאַסן. װי קינדער װאָס װילן זיך נישט באָדן, „מ׳האָט אַ װײַב, מ׳האָט אַ בעט און אַ גביריש הױז, חאָבן געשמועסט זעבראָװסקי סטראַזשניק און דער כלבים-שלעגער׃ נאָר דו הערסט נישט, און די שטערן זײַנען דיר נאָכגעגאַנגען III דײַן אַלטקײט ברעכט זיך אױפֿצושטײן מיטן ערשטן קרײַ פֿון האָן. לעבעדיק די בלומען… און אַ בעט פֿון פֿײַנעם מאַהאַגאָן און דרימלט אײַן אין קילן בעטצײַג, װי אין פֿרישן טיפן שנײ. אַרױסגעװאָרפֿן, װי אַ פֿליג פֿון אַ שײנער בלאַנקיקער גלאָז טײ. מוזן עסן בױמאײל-חלה און ער לױפֿט אַרום און שרײַט׃ װען האָב און גוטס און גאָט אַלײן געהערט צו די אָרעמעלײַט… טאָ װי אַזױ איז הינטער דער פּאָלע פּלוצים דאָרט געװאָרן בײַ אײַער פֿרײדען און איר טראָגט עס צו אַ שװאַכער קימפּעטאָרן. װען דער פּדיון ברענט אין קראָם, װעט ער דאָך לײגן אַלץ אין דר׳ערד. דו ביסט געװען אין נגידישן הױז׃ אַ גרױזאַמער בריװ אין אַ צאַרטן קאָנװערט… נו, מילא, כאָטש איז פֿרײַטיק, װײס מען׃ קוקט אפֿרים׃ אין הימל באַקט מען חלות און בײַם לאַטוטניק יאָסל שטאַרבט מען פֿאַר אַ ביס. אַ קאָפּיקע אין אַ קױלעטש! אין װײַסע װאָלקנס רױטע צונגען צינדט מען ליכט אין זילבער-לײַכטער. איז מילא כאָטש, נו פֿרײַטיק, זעט מען נאָר אַ גאַנצע װאָך? רחמנא ליצלן׃ ביז תחילת נאַכט — רק ער זאָגט, V שטיל און הײליק מאַכט זיך אױף דער טאָג, די זון קומט אַרױס װי אַ שײנער געדאַנק. שטעטל האָט דעם שלאָף אָפּגעטרײסלט פֿון די אױגן, אַפֿילו האָרקי שנײַדער, װאָס זיצט שױן בײַ דער מאַשין געבױגן, און װאָס טוט אפֿרים גאָלדברוך? ליגט דער האַלבטאָג אין דער װעלט און ברענט פֿאַר כּעס און איז פֿאַרשעמט׃ ער האָט מענטשן ליב און לײַכט פֿאַר ליבשאַפֿט, נאָר זײ צו אים זײַנען פֿרעמד, דער מסחר גײט אין מאַרק — אין הימל גייט די זון און שיט אין גײן װאָלקנס כאַפּן שטראַלן אין מױל װי יונגעלײַטלעך פּריצן, און װאָס טוט אפֿרים גאָלדברוך? נאָר דער טאָג ט׳זיך שענער נאָך געענדיקט װי זיך אָנגעהױבן. און די װײכע רגעס פֿון פֿאַרנאַכט פֿליען איבער זײ װי טױבן, פּאַסט-צו די זון פֿון בלוט אַ שליסל… אין-זיך-פֿאַרטראַכט און פֿרום געבױגן מיט אײן שעה פֿריער, װי קלוגע װאָס האָבן אַ סך געזען און כאַצקל קופּערמינץ באַגרײפֿט נישט, װאָס פּלוצלינג איז מיט אים געשען, — און קוקט אין מאַרק׃ שאָטנס פֿאַלן צו דער ערד האַלדזנדיק די שטײנער; און װאָס טוט אפֿרים גאָלדברוך? VI װי קען אַ מענטש אַ גאַנצן טאָג אױף אַ פֿאָדערשטן שײנעם צאָן קוקן מענטשן דער װעלט אין מױל, גלײַך מוז זײַן די לײמענע שיסל׃ װען אױך דער צאָן אױף יענער זײַט ס׳װאָלט זיך פֿאָדערשטער צאָן אַרױסגעריסן װאַרפֿט מען לאַנגזאַם האַרץ װי פּאַסן האָניק טאָ װי קען אַ מענטש אַ גאַנצן טאָג VII — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — — |