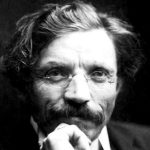

Photo: William E. Sauro/The New York Times.

אַבֿרהם סוצקעװער

1913-2010

Abraham Sutzkever, one of the greatest Jewish poets to have lived, passed away Wednesday morning in Tel Aviv. He was 96. His life story reflects an important element in the annals of the Jewish people during the 20th century.

Sutzkever was born in 1913 in the town of Smorgon, near Vilna, during the Czarist empire. After being deported to Siberia as a child, he later returned to independent Poland and began to write. In 1941 he was incarcerated in the Vilna ghetto, where he soon became active, notably in saving treasures from the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. Following the liquidation of the ghetto, he and his wife Friedke escaped to the forests, where he fought alongside the partisans and was rescued by a special Soviet plane at Stalin’s personal order. After the war, he worked to rehabilitate Jewish life in Europe, testified at the Nuremberg Trials and immigrated to Israel in 1947.

He continued to write in Yiddish in Israel, and founded a new literary group called “Young Israel.” He viewed his work as another link in the great chain of world culture. It was not by chance that he called the journal he founded in 1949 “Di Goldene Keyt” (“The Golden Chain”).

However, despite all his public activity, and even though he effectively functioned as a Greek tragic chorus, his poetry always retained its inimitable individuality. As a poet, he had already excelled in the journal “Young Vilna,” in contrast with the radical modernist tone of his colleagues, using an aesthetic approach which placed the nature outside the Jewish village at the center and arranged it in classical meter.

His subject matter changed once in the Vilna ghetto, but his lament remained extraordinarily personal – as in “Beneath the Whiteness of Your Stars” (which was set to music in the ghetto), a poem of prayer, of escape from his pursuers and of escape from God.

Sutzkever‘s work was already considered classic while he was still a young man, as his close friend Marc Chagall said (by the 1930s his work had already been translated into Russian by Boris Pasternak). But after World War II he remained one of the central – and only – spokespersons of a language that had lost most of its speakers. This was how he was perceived throughout the world and nowhere more so than in Israel. Beginning in the 1940s, his poetry was translated by the greatest Hebrew poets, among them Nathan Alterman, Avraham Shlonsky and Leah Goldberg. “Sutzkever,” Chagall wrote elsewhere, “saw the face of that last day, but in a goodly time also embarked on a new day.”

Thematic metamorphosis

In Israel, his themes underwent another metamorphosis, with the earlier Siberian wilds giving way to the landscapes of the Negev and Galilee. A prolific writer, he constantly renewed himself, even in his last years. His “Poems from a Diary,” written in the 1970s and ’80s, are pellucid voices of the past and the future alike. In one of these poems he wrote: “Who will last? And what? The wind will stay, / And the blind man’s blindness when he’s gone away, / And a thread of foam – a sign of the sea – / And a bit of cloud snarled in a tree. […] / Of all that northflung starry stuff, / The star descended in the tear will last. / In its jar, a drop of wine stands fast. / Who lasts? God abides, isn’t it enough?” (Translation by Cynthia Ozick; quoted in “The Fiddle Rose: Poems 1970-1972 by Abraham Sutzkever,” selected and translated by Ruth Whitman, Wayne State University Press.)

Sutzkever, who had been one of the gifted young practitioners of Yiddish poetry before World War II, eventually became the dean of Yiddish poets. However, his work did not age, it continued to stir interest around the world and was translated into countless languages. Sutzkever was awarded the Israel Prize in 1985, and his poetry seems to have been recently rediscovered in Israel. A selection of his work was published in 2005, translated into Hebrew by veteran and young poets alike.

The poet and editor Dory Manor, a friend of Sutzkever‘s in recent years, said after his death: “It feels to me as if a divine providence has been removed – a period that ended long ago and now comes its final wax seal. As long as Sutzkever lived among us, something of the great world spirit lived here. Now that he has gone, that too has gone. Sutzkever must be spoken of in the same breath as the great poets of the 20th century, be mentioned in proximity to such poets as Rilke, T.S. Eliot, Mandelstam and Paul Valery. He was a master artist, like a Renaissance poet, but could also be no less of a wild, boundary-breaching modernist than Avoth Yeshurun or Yona Wallach. I have no doubt that he was the greatest poet who ever lived in Israel. The obscure life that Sutzkever led in Tel Aviv over the past few decades is a melancholy metaphor for the oblivion to which the great Yiddish culture has been consigned. Maybe now more Israeli readers will be privileged to become acquainted with him and with that culture.”

- A link to a follow-up article on Avrom Sutzkever in Haaretz:

http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/1145689.html