Drops of Joy – Poetry of Moshe Shklar

“אַ הויז פֿון װײַסן פּאַפּיר” – אַ צופּאַסיקער מעטאַפּאָר אויף אָנצופֿאַנגען געדאַנקען װעגן דעם באַװוּסטן ייִדישן דיכטער, שרײַבער, און קולטור־טוער, משה שקלאַר, מיט װעמען איך האָב געהאַט דעם גרויסן כּבֿוד זיך צו באַפֿרײַנדן און טייל מאָל בשתּפֿות געאַרבעט אין לאָס אַנדזשעלעס די לעצטע 20 יאָר פֿון זײַן לאַנגן, שעפֿערישן לעבן.

“אַ הויז פֿון װײַסן פּאַפּיר” – אַ צופּאַסיקער מעטאַפּאָר אויף אָנצופֿאַנגען געדאַנקען װעגן דעם באַװוּסטן ייִדישן דיכטער, שרײַבער, און קולטור־טוער, משה שקלאַר, מיט װעמען איך האָב געהאַט דעם גרויסן כּבֿוד זיך צו באַפֿרײַנדן און טייל מאָל בשתּפֿות געאַרבעט אין לאָס אַנדזשעלעס די לעצטע 20 יאָר פֿון זײַן לאַנגן, שעפֿערישן לעבן.

װײַסע פּאַפּיר איז ראשית־כּל אַ דיכטערס הויפּטער מכשיר; אַ “הויז פֿון װײַסן פּאַפּיר” — די פֿאַקסימילע װעלט װאָס יעדער איינער – ניט נאָר אַ קינד – בויט פֿאַר זיך כּדי צו קענען אָנכאַפּן און זיך ראַנגלען מיט עיקרדיקע אמתן. װען עס גייט זיך צעפֿאַלן – װי עס מוז – װער בעסער פֿון אַ דיכטער קען עס צו רעכט מאַכן און רעטן?

עס װייטיקט מיר צו דערמאָנען אַ דיכטער װאָס האָט געשטאַמט פֿון אַ ייִדישן דור װאָס איז כּמעט װי נישט איצט פֿאַרשװוּנדן. דער דאָזיקער דור האָט אויפֿגעבליט אין אַ געװיסער צײַט און מקום און איז געװען ממש אייגנאַרטיק. יעדער דור איז אין אמתן אייגנאַרטיק, אַװדאי, אָבער דער – מײַן עלטערנס דור – פֿון װעלכן משה שקלאַר איז געװען אַ טייל איז געװען אַזוי משנה פֿון די דורות װאָס זענען געקומען פֿריער אָדער דערנאָך, אַז ס’איז אַפֿילו ניט צו פֿאַרגלײַכן. און מ’קען נישט אָפּזונדערן משה שקלאַרן פֿון זײַן דור.

זײַן אויפֿטו אַלס אַ שרײַבער און פּאָעט—12 ביכער, אַ נאָװעלעס, זכרונות–, זײַן געזעלשאַפֿטלעכע אַרבעט –רעדאַקטער פֿון באַרימטן ייִדישן זשורנאַל חשבון פֿאַר 20 יאָר – אַלץ האָט געשטאַמט פֿון אַן אוניקאַלן װעלטלעכן ייִדישן קװאַל װאָס האָט דעמאָלט, אין זײַן יוגנט, געפֿליסט, און װאָס איז אין קורצן מיט גװאַלד שיר װי אין גאַנצן דערשטיקט געװאָרן.

האָט ער פֿאַרשטאַנען, משה, גלײַז װי זײַן באַליבטן ייִדישן דיכטער און פֿרײַנד, אַבֿרהם סוצקעװער, אַז ער מוז זײַן אי דער װײַטערדיקער טרעגער פֿון זײַן ירושה, אי דער באַװיינער פֿון דער שחיטה פֿון דער מערהײַט אַנדערע טרעגערס פֿון זײַן דור.

און מיר מוזן זײַן דאַנקבאַר – און איך פּערזענלעך בין זיכער דאַנקבאַר – װאָס ער האָט אָנגענומען אויף זײַנע שמאָלע פּלייצעס און זײַן אָנגעשטרענגטן האַרץ אַזאַ בכּבֿודיקע און װאָגיקע עובֿדה. אפֿילו פֿון די ענצלנע פֿון זײַן דור װאָס האָבן יאָ איבערגעלעבט די שחיטה, האָבן נאָר אַ הויפֿן זיך אָפּגעגעבן אַ גאַנץ לעבן צו דער הייליקער אַרבעט.

און עס איז הייליק. איך װייס אַז משה שקלאַר, אַלס אַ לינקער, איז ניט געװען קיין גלויביקער, אָבער ער האָט געמוזט זייער גוט פֿאַרנעמען דעם גײַסט װאָס האָט געהאָנגען אין זײַנע כּסדערדיקע דערגרייכונגען מיט זײַן קונסט און פֿאַר ייִדישער קולטור.

פֿון אַ מער פּערזענלעכן קוקװינקל אויף משה שקלאַרן דעם מאַן, און ניט נאָר דעם פֿאַרטרעטער פֿאַר זײַן גאַנצן מיזרח־אייראָפּעישן ייִדישן דור, קען איך דערציילן אַז מיט מיר האָט ער זיך געװענטלעך געהאַלטן פֿאָרמעל און סטאַטעטשנע – מיט דער סיװיליזירטער פֿאָרמאַליטעט װאָס מ’זעט שוין נישט אַזוי אָפֿט.

ס’איז צו פֿאַרשטיין – אַחוץ דעם װאָס ער איז געװען פֿון אַן עלטערן דור און אַ װיכטיקער פּערזענלעכקייט אין דער ייִדישער סבֿיבֿה אין ל.אַ., איז ער אויך געװען דער רעדאַקטער פֿון זשורנאַל (חשבון) װאָס האָט אַמיינסטנס געדרוקט מײַנע לידער. און צו אים האָב איך זיך שטענדיק געקאָנט װענדן מיט אַ שאלה װעגן עפּעס ייִדישלעך – װי זיך צו באַנוצן מיט אַ װאָרט אין אַ שריפֿט, װי איבערצוזעצן אַ װערטל, און אַ.ז.װ.. ס’האָט אים זייער געפֿאָלן װען עמעצער האָט זיך נאָך פֿאַראינטערעסירט אין אַזעלכע שאלות און ער האָט זיי אָנגענומען ערנסטערהייט.

איז װען ער האָט זיך געװיצלט – און דאָס איז דאָך נישט געװען אַזוי זעלטן, װײַל אָפֿט האָט זיך בײַ אים אַרויסגעכאַפּט עפּעס אַ הומאָריסטישע באַמערקונג – איז עס דאָך געװען װי מיטאַמאָל װאָלט זיך דערװיזן אַ היימלעכער שפּילפּלאַץ אויף אַ גאָר פֿאַרנעפּלטן װעג.

איינע פֿון מײַנע באַליבסטע זכרונות פֿון משה שקלאַרן איז װען מיר האָבן אים פֿילמירט פֿאַרן ייִדישן אינסטיטוט פּראָיעקט “לעבעדיקע ייִדישע אוצרות” (װאָס מיר װעלן בקרובֿ אַרויפֿשטעלן אויף אונדזער יו־טוב טשאַנעל פֿון אונזער װעב-זײַטל.)

נאָך אַ לאַנגן, אינטענסיװן אינטערװיו פֿון עטלעכע שעה װעגן זײַן לעבן און קולטור אַרבעט מיט ייִדיש, האָט ער זיך אָנגעטאָן אַ פֿאַרטעך, און צוזאַמען מיט זײַן פֿרוי דאָרקע, זיך צוגעשטעלט אין קוך געדולדיק און

איידעלערהייט זיך נעמען צו מאַכן קניידלעך. במשך פֿאָרמירן די פּערפֿעקטע קיילעכדיקע בעלעמלעך װאָס דאָרקע האָט דערנאָך אַרײַנגעװאָרפֿן אין זודיקן װאַסער, האָט ער זיך, מיט אַ ברייט שמייכעלע, כּסדר געװיצלט. און געװען איז ער אַזוי באַקװעם אין זײַן פֿאַרטוך און זײַן מיטהילף אין קוך, אַז ס’איז געװען קלאָר אַז דאָס טוט ער נישט צום ערשטן מאָל.

האָב איך דעמאָלט פֿאַרשטאַנען אַז דאָס איז טאַקע זײַן אמתע טבֿע, װאָס לויערט שטענדיק אונטערן ערנסטן געזיכט.

אַדרבא מוזן אַ צאָל משה שקלאַרס לידער זײַן קלאָגלידער – פֿאַר זײַן אָפּגעהאַקטן דור און פֿאַרניכטערטע באַליבטע, פֿאַר דער ציװיליזאַציע װאָס האָט איבערנאַכט חרובֿ געװאָרן, פֿאַר דעם רײַכן נוסח פֿון לעבן װאָס װעט געזעלשאַפֿטלעך קיין מאָל ניט מער עקסיסטירן בײַ ייִדן.

און ס’זענען בײַ אים פֿאַראַן לידער דורכגעװעבט מיט מעלאַנכאָליע, װי דאָס ליד װאָס איך האָב שטאָלץ פֿאָרגעלייענט פֿאַר עולמס איבער דער װעלט – לעצטנס אין יאַפּאַן – “איך און װאַן גאָגס שיך”. פֿונדעסטװעגן, האָט דאָס ליד מער צו טאָן מיטן המשך פֿון שעפֿערישקייט איידער מיט טרויער.

“White paper”, how apt a metaphor with which to introduce remarks about the renowned Yiddish poet, writer, and cultural activist, Moshe Shklar, whom I had the great honor to befriend and occasionally partner with in Los Angeles during the last 20 years of his long, creative life.

“White paper”, how apt a metaphor with which to introduce remarks about the renowned Yiddish poet, writer, and cultural activist, Moshe Shklar, whom I had the great honor to befriend and occasionally partner with in Los Angeles during the last 20 years of his long, creative life.

White paper is first of all a poet’s main tool; and a “house of white paper” can be understood as the facsimile world that everyone — not just a child — erects for themselves in order to both perceive and grapple with essential truths. When it is about to disintegrate – as it must — who better than a poet to rescue and restore it?

It pains me to convey something about a poet who stems from a generation that has nearly vanished. This generation blossomed at a particular time and place and was especially unique. Certainly every generation is unique, but that specific Jewish generation – my parents’ generation — of which Moshe Shklar was a part was so different from the generations that came before or after it, that there is no comparison. And one can’t separate Moshe Shklar from his generation.

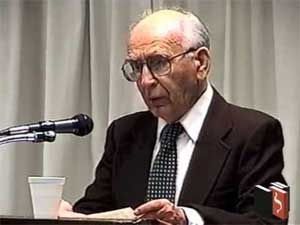

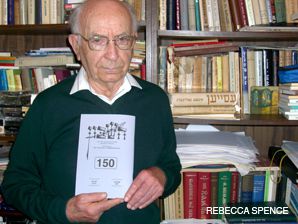

His accomplishments as a writer and poet: 12 books of poetry, novellas, and memoirs in Yiddish; his work for the community: editor of the esteemed Yiddish literary journal Kheshbn for 20 years — everything stemmed from a unique secular Yiddish source, which, at the time of his youth, flowed freely, and that shortly thereafter was nearly entirely choked off.

Therefore Moshe understood, like his beloved idol and friend, the great Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever, that he must be both the bearer of his inheritance and the lamenter for the slaughter of the majority of other bearers of his generation.

And we need to be thankful – and I personally am certainly grateful – that he took upon his narrow shoulders and his over-strained heart such an honorable and weighty task. Even among those relative few who did survive the slaughter, only a handful devoted their entire lives to this holy work.

And it is holy. I know that Moshe Shklar, a political lefty, was not a true believer, but he had to have perceived the spirit that was attached to his daily achievements in his creative work and for Yiddish culture.

On a more personal note about Moshe Shklar the man, and not just the representative for his entire Eastern European Jewish generation, with me he generally kept a quite formal and dignified manner – the civilized formality that one doesn’t encounter very often any more.

Understandably – aside from being an elder and an important personage in the Yiddish community in L.A., he was the editor of the journal (Kheshbn) that published most of my poems, and he was the one I could always turn to for something to do with Yiddish – how to use a certain word in a text, how to translate an expression, etc.. He was always happy that someone still deigned to ask these kinds of questions.

So when he joked around – and this wasn’t all that seldom as he often let slip some humorous comment – it was as if suddenly a thick fog had parted to reveal a lively playground.

One of my favorite memories of Moshe Shklar is when we filmed him for the Yiddish Institute’s project “Living Yiddish Treasures” (which we will soon post on our youtube channel associated with our website).

After a lengthy, intensive hours-long interview about his life and association with Yiddish, he donned an apron, and together with his wife Dorke, went to the kitchen to patiently and skillfully proceed to make matzoh balls. While forming the perfectly round little balls which Dorke then tossed into the boiling water, with a wide smile on his face, he kept making jokes. And he was so comfortable in his apron and his task in the kitchen that it was clear that this was not the first time he had done this.

That was when I understood that this is his true nature -always hovering beneath his serious countenance.

Nonetheless, it stands to reason that many of his poems bemoan the severed generation, the annihilated loved ones, the civilization that was destroyed overnight, the rich way of life that will never manifest again in Jewish society.

And among his poems are those woven through with melancholy, like the poem I proudly read to audiences around the world – most recently in Japan: “Me And Van Gogh’s Shoes”. However, this poem has more to do with the continuity of creativity rather than with grief.